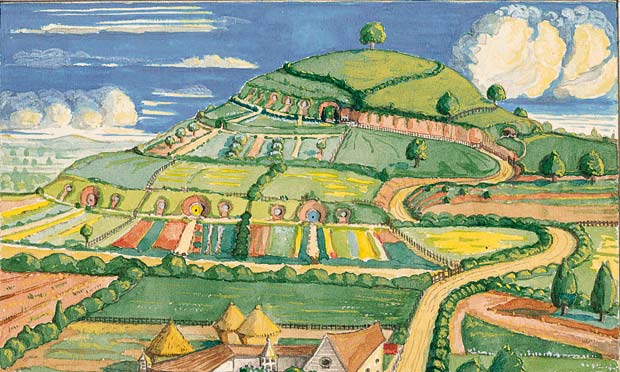

The Shire, illustration by J.R.R. Tolkien

The Shire, illustration by J.R.R. Tolkien

I am absolutely blown away by the number of people who have read my piece about J.R.R. Tolkien’s lost Rotterdam Hobbit Dinner speech. Right now the Huffington Post article has received over 50 thousand Facebook likes. In that speech Tolkien read a lost poem about “cold-hearted wizards” who have corrupted our own world. When Mark Ostley of The Middle-earth Network first told me about the recording, he said that Tolkien’s lost poem reminded him of the chapter in my book “Tearing Down Sharkey’s Rules.” Here’s the whole chapter, excerpted from my book.

The Wisdom of the Shire is available in hardcover, paperback, Kindle, Nook and audiobook. Several foreign translations (Italian, Spanish and Portuguese) can be found on iTunes.

Chapter 6: Tearing Down Sharkey’s Rules (© Noble Smith)

Frodo, Sam, Merry and Pippin truly are fighting for something invaluable during the War of the Ring—for friendship and the love of the Shire. And that is why they are so crushed when they return after their long absence to find the evil wizard Saruman has taken over their small country with a gang of Big People. Saruman has imposed a fascistic strong-arm rule with the sole intent of destroying the Shire and teaching the Hobbits a lesson—a punishment for their part in the wizard’s downfall.

Hobbits live in an egalitarian society where the poorest amongst them, like the old gardener Gaffer Gamgee of Bagshot Row, have the same rights and intrinsic value the wealthiest inhabitants of the Shire, such as the famous Bilbo Baggins of Bag End. They’ve figured out a rule of thumb for making many things work, and they have a collective agreement to keep doing it that way. The farmer, the miller, the gardener and the innkeeper are all a part and parcel of the Shire—a sustainable and self-sufficient “nation” of independent people, all of them living and working together, never fighting amongst themselves. A place where the most important building isn’t a public hall, but a public house. [1]

The Hobbits don’t have a government. Instead they hold meetings called “moots” where the Shire-folk gather together to decide important matters and sometimes elect a nominal leader called a “thain.” There are certain basic laws called the Rules that have come down from ancient times when they were reigned over by a king, but the last one of those Men died a thousand years before, and Hobbits could care less if no king returns.

They believe in free will, but there is a robust social agreement and longstanding traditions preventing people from stepping on each other’s shoeless toes. The Hobbits have a deep moral code that includes the treatment of animals. [2]

Tolkien based the Shire on an idealized version of an England that existed before the Norman invasion of 1066, when the local population of Anglo-Saxons lived under a kind of early democratic monarchy. Like Middle-earth these people dwelled in regions called “shires” with “moots” and “thains.” The great majority of them were industrious farmers. England was prospering in the 11th century and had been at peace for two generations until William the Conqueror came across the Channel, killing the Anglo-Saxon King in battle, vanquishing his army, and imposing French rule and language on the defeated natives.

As a boy, Tolkien—the cheeky lad—participated in a school debate where he argued against the French invasion and its aftermath, like some kind of alternate reality historian. In his fantasy the Normans lost the war and the Anglo-Saxons kept their pleasant way of life intact. Later in life Tolkien would invent his Shire—the beating heart of Middle-earth. [3]

Try to imagine the Shire as Tolkien, or rather a Hobbit, would have seen it. The place is rich with natural resources—dense woodlands interspersed with fertile soil for growing crops. There is no unemployment and food is plentiful for those willing to put in a hard day’s labor. It’s a safe place too—a Hobbit can walk from the East to the Westfarthing under starlight without fear. (Hobbits don’t murder each other, at least not in the Third Age of Middle-earth.) There is no standing army or police force, only twelve Shirriffs [4] to patrol the entire Shire on foot, mainly to round up wayward livestock.

The Shire-folk practice sufficiency, a concept that means, “If you have enough you don’t need to take any more.” Businesses consist mainly of craftspeople, and these family-run enterprises remain small generation after generation, because nobody sees any need to expand them. People concentrate on the growing of food (and the eating of it), making things with their hands and living life to its fullest. They have a whiff of the Luddite about them and are wary of any machines more complicated than a loom or a mill.

There’s a profound tranquility to be found here. A rhythm to the way of life that’s been going on interrupted for over a thousand years. The Hobbits have little concern for what’s taking place outside of the Shire. They very rarely venture further than the Mannish town of Bree to the East, or the borderlands to the West. From here the Hobbits can look across the rolling hills toward the direction of the Sea. If the moon is out they might catch a glimpse of Elven towers atop The Tower Hills—a reminder of the Elder Days and the mysteries of the past—shimmering in the distance.

When Frodo and his friends return to the Shire after the War of the Ring they are devastated by the destruction they find. The inns have all been shut or converted into factories, even The Green Dragon is vacated—its windows all broken. Houses are abandoned and burned to the ground. Trees have been wantonly chopped down. Ugly smokestacks pour black grime into the sky. Hobbiton has become the Detroit of Middle-earth. For Sam, this is worse than Mordor. Frodo tells him this is Mordor—the malice of Sauron has crept into their home.

Saruman, having lost his fortress of Isengard and his army of Orcs, now lords over the Shire with a gang of brutes who call him by the name of “Sharkey.” The wizard has been enforcing his will with a set of officious orders. These are “Sharkey’s Rules.” We only get a glimpse of these edicts, but from the reaction of the returning Hobbits we understand they are numerous and frivolous—the malignant efforts of an evil mind to impose a bureaucratic damnation on an autonomous and freethinking people. [5]

Tolkien was a self-described anarchist. He wasn’t your typical revolutionary, of course. He was speaking tongue-in-cheek. What he meant was he didn’t want the “whiskered men with bombs” in control of the world, inflicting a way of life that defied common sense and common decency. You can see reflections of this repugnance of despotic leaders in his stories. The venal Master of Laketown, the archetype of the deep-seated bureaucrat, is the minor villain of The Hobbit. He embezzles funds meant to feed the homeless and flees from his burning city, leaving his fellow citizens to die.

Denethor, the tragic figure of The Return of the King, is the power-hungry Steward of Gondor—an entrenched functionary—who, seeing his realm and control slipping away, abandons his constituency in their time of extreme crisis, burning himself alive, “Like a heathen king of old.” Even the Steward’s pompous death was an aspirational act. [6]

Saruman the wizard is an autocrat seeking power by any means necessary (like secretly creating his own hybrid army of Orcs, or placing his agent Wormtongue in Rohan). With the Hobbits, though, his influence is more insidious. He’s been spying on them for decades, having grown suspicious of Gandalf’s dealings with the Halflings. When he takes over the Shire the wizard knows that the way to break generous and kind-hearted people is to turn them against each other—trick them into becoming spies and sneaks and tattle-tales, rewarding the worst kind of behavior, and punishing the honorable. In that way he seizes control of a great many Hobbits with only a handful of followers at his back and imprisons all of the dissenters in isolation cells called “the lock-holes”—the Gitmo of Hobbiton.

What is Saruman creating, one wonders, inside all those factories belching black fumes and polluting the once pristine little streams and ponds of Hobbiton? We’ll never know for sure. Perhaps he’s just burning up all the trees out of spite, for the sheer wicked joy of making smoke. Or maybe he’s making diabolical weapons to sell to Gondor’s enemies—a sort of Hobbiton arms manufacturer. Whatever the case, Saruman & Co. is like an evil conglomerate that moves into a pretty little rural town, builds a factory on the river, guts the natural resources and poisons the soil and water until there’s nothing left but a derelict Superfund site.

The first thing Pippin does when he sees a list of Sharkey’s odious rules posted on the walls of a Hobbit guard-house is to rip them all down in a fit of indignation. Then he proceeds to break rule Number 4 by burning up all the firewood. The Hobbits are despondent. They’ve gone through pain and death to come home to this devilry—these hateful stipulations. No pipe-smoking! No beer! And a band of Shirriffs bickering and spewing “Orc-talk.” What has become of their cherished country?

Bill Ferny, the squinty-eyed pony abuser from Bree is the first invader they meet at the newly constructed iron gates blocking the passage of the River Brandywine. The only way to deal with a bully like Ferny, Merry swiftly decides, is with the threat of violence. And the cowardly Ferny runs away as fast as he can from the Fearless Four.

The gang of murderous thugs the companions find ensconced in Hobbiton are more violent and hell-bent than Ferny, however. And it takes a concerted effort of Hobbits, led by Samwise, Merry and Pippin to kill, to capture and drive them out (and not without loss to the Shire-folk). It’s a bloody and violent little revolution, and a melancholy way for the War of the Ring to finally end.

The last invader they must deal with is the despicable Saruman. [7] What takes place next is a kind of Shire trial where all of Hobbiton stand as witnesses and jury with Frodo acting as the judge. The Hobbits want Saruman to be put to death for his crimes, but Frodo asks the Hobbits to spare the wizard’s life and send him away from the Shire and into exile. Frodo does not wish to see more savagery—he abhors the thought of his beloved and gentle people going down a slippery slope of brutishness where they become like the merciless Saruman who (Frodo explains to his countrymen) was once of an honorable kind and might still be capable of redemption.

Saruman, humiliated by the Ring-bearer’s benevolence, tells Frodo-the-judge he’s become “wise, and cruel.” But the wizard, his reason clouded by a corrupting lust for power, is completely in the wrong. He’s become as deluded and as unprincipled as any of the Men he was sent to Middle-earth to give counsel to. Frodo’s journey through the world of the Big People has indeed taught him wisdom. But Saruman is the one who is cruel, and therefore projects that hateful attribute onto others. Hobbits, at least the ones we love, do not have the capacity for cruelty, and neither should we. [8]

The change in our own society is less dramatic, of course, but just as pernicious as Sharkey’s Rules. Our rights and privacies have slowly been stripped away through edicts such as The Patriot Act. With a deficit over 15 trillion dollars, the banksters have perpetrated the greatest fraud in the history of the world, mortgaging our children’s futures for personal gain. And corporations continue to cut away workers’ rights and benefits to meet the bottom line. When are we going to tear down Sharkey’s Rules in our own lives and build bridges to new and healthier ways of doing business and dealing fairly with other nations?

In the days after the “Scouring of the Shire” Sam laments that only his great-grandchildren will see the beauty of Hobbiton as it was before the desecration of Saruman. But he rolls up his sleeves and starts to work straightaway, probably with this saying of the Gaffer in mind: “It’s the job that’s never started as takes the longest to finish.”

The Hobbits—and all of their kindred—react to the calamitous situation with the grit and determination they’ve shown throughout the stories . . . in just the same way humans always seem to pull together after some terrible natural disaster. The industrious Shire-folk set to their multitude of tasks, clearing away the ugly sheds and factories, cleaning up the filth, replanting and mending.

The Hobbits have come to understand they can’t keep the world fenced out anymore, but at least they now know how to deal with the rest of Middle-earth. They’ve become a little wiser, but they’ve done so without tainting the essence of what makes them Hobbits—the abiding goodness intrinsic to the people of the Shire.

Sam is eventually appointed mayor of the Shire, a political position he holds for almost fifty years, until he resigns at the ripe old age of ninety-six. We can imagine Sam was a wonderful mayor. Without a doubt more trees were planted under his tenure than any other mayor in the history of the Shire. Fireworks were certainly lit off on every public holiday and festival. Presents given out on his birthday were doubtlessly of great practicality and thoughtfulness. And I’m pretty sure the only decree he ever submitted for ratification in his long term of office was “No new rules.”

The Wisdom of the Shire Tells Us…“Baffling rules made by flawed men sometimes need to be torn down and replaced with the standards of common sense.”

The Wisdom of the Shire is available in hardcover, paperback, Kindle, Nook and audiobook. Several foreign translations (Italian, Spanish and Portuguese) can be found on iTunes.

Trivia, inserts and sidebars for Chapter 6: Tearing Down Sharkey’s Rules

[1]Some of the best known inns of the Shire were: The Golden Perch, The Floating Log, The Green Dragon, and The Ivy Bush.

[2]Hobbits, we are told, did not hunt animals for sport.

[3]Tolkien attended secondary school at King Edward’s School in Birmingham, England where the school song proclaims there are “No fops or idlers” in attendance.

[4]Shirriff: A sort of Hobbit policeman. Based on the Old English for “shire reeve.”

[5]Orcs were created eons before by the evil demigod Morgoth to serve as his army in his fight against the Elves. Sharkey is an Orkish word meaning “old man.”

[6]Faramir’s father Denethor burned himself alive with a palantir or “seeing stone” clutched in his hands. It was said if someone tried to look into that palantir thereafter, all they would see were Denethor’s old hands withering in the flames.

[7]Frodo did not participate in this fight. After the Ring was destroyed he gave his sword “Sting” to Sam and essentially lived out the rest of his days as a pacifist.

[8]The actor Christopher Lee, who played Saruman in The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit, is the only actor in the films to have actually met J.R.R. Tolkien. Lee reads The Lord of the Rings every single year.