Last week I found a first edition of A Tolkien Bestiary at my local used bookstore. “Perfect Christmas present for my son,” I thought and snatched it off the shelf. I had originally bought the Bestiary when I was twelve years old (a year after it was published in 1979). It quickly became ensconced in the stack of Tolkien-themed books that I kept in a special place by my bed for late night flashlight reading—books like J.E.A. Tyler’s The Tolkien Companion (which I recently wrote about here for The Huffington Post) and Karen Wynn Fonstad’s The Atlas of Middle Earth.

Coincidentally, David Day—the author of A Tolkien Bestiary—started following me on Twitter a few days after I bought that copy of his classic. So I decided to reappraise this tome that I (and many other Tolkien fans) have loved for over three decades.

Day’s book is a true “bestiary” and was based (as he states in his preface) “…on the Greek-Egyptian ‘Physiologus’ of the second century AD. It codified the ancients’ knowledge of magical and monstrous animals and races.” In it you’ll find entries for things like “Vampires” and “Horses”—generalized entries that do not appear in other Middle-earth dictionaries (like The Complete Guide to Middle-earth). This makes delving into the Bestiary more like reading a fascinating novel than a tedious lexicon.

A Tolkien Bestiary is filled with stunning artwork that was created by a team of 11 artists, and these illustrations still seem fresh and interesting even after all these years. Look at how the Halfling in this image brings to mind Elijah Wood as Frodo. (Remember: the book was published two years before the actor was born!)

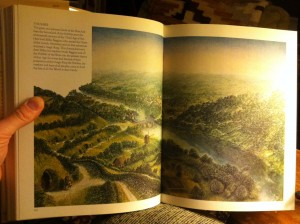

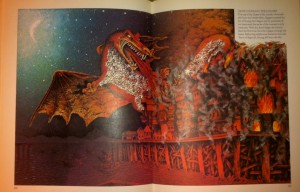

I used to pore over these paintings and drawings for countless hours, marveling at a Dürer-like line drawing of a Dunlending warrior’s wicked looking armor; or gazing at a beautiful painting of a verdant and sunny Hobbiton as seen from a soaring bird’s POV (see photo at the top of this blog); or a dynamic action scene of Smaug the Golden attacking Lake-town, the Dragon’s belly encrusted with gemstones. (Don’t be surprised if you see a shot exactly like this in The Hobbit 3.)

Day wrote the book when he was thirty years old (still a tween by Hobbit standards), but he was obviously already a Tolkien expert. You only have to read his entries on Dragons or Ents or the Noldor (wonderfully long and enlightening essays) to know that here was a Middle-earth scholar—someone capable of gleaning information from all of Tolkien’s works and consolidating the stories into highly readable yet purposefully antiquated prose.

This slightly archaic style makes you feel as though A Tolkien Bestiary could have been compiled by an inhabitant of the Shire (or even of Gondor): a companion piece to the fabled The Red Book of Westmarch. A Tolkien Bestiary reads like an exciting artifact from Middle-earth.

The two charts placed at the start of the book, provided by the author for “chronological orientation” of Middle-earth, are terrific visual aids created long before the PowerPoint era. They are graphic timelines that take the events from The Silmarillion to the end of The Lord of the Rings and assemble them into coherent and easily understandable diagrams.

A Tolkien Bestiary really stands the test of time. It’s a classic in its own right and the perfect companion for Tolkien’s Middle-earth canon. I had the pleasure of corresponding with David Day via Twitter and he told me that he wrote the entire book in a coffee house that had once been the bookstore of the great Orwell. Most of us have heard the story of J.K. Rowling writing her first Harry Potter book in The Elephant House coffee shop in Edinburgh. Well, David Day beat this writerly feat by over twenty years!

Day has a new a new book called Nevermore. It’s about how the fates of animals are wholly linked to the history of humankind. Ex-Python and author Michael Palin said Nevermore is “a beautiful and timely book.” I ordered a copy and can’t wait to read it.

You can buy a copy of A Tolkien Bestiary from almost any online retailer. And if you’re lucky enough, you might find a perfect first edition at your local used bookstore.