I have seen the new edition of The Hobbit illustrated by Jemima Catlin, and I enthusiastically declare that it is a splendid thing! I received an advance copy of the book from the publisher (HarperCollins UK) in the mail the other day—and getting it felt like Christmas.

I have many editions of The Hobbit in my collection, from Alan Lee’s handsomely illustrated edition, to the bizarre Rankin and Bass animated film book tie-in, to the one with Michael Hague’s sumptuous paintings. All of them have a place in my heart for one reason or another, along with my favorite Tolkien artist Pauline Baynes’s work. (She created an amazing cover for the Penguin edition of The Hobbit but, sadly, never did an illustrated version).

And now I have this magnificent new version of The Hobbit from Ms. Catlin to sit beside the others on my shelf of Tolkien books.

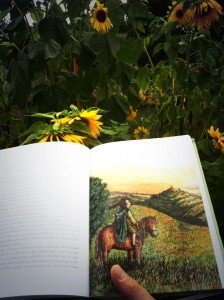

There’s something about Catlin’s inspired work that filled me with a childlike joy—the same joy that I had the first time I saw an edition of The Hobbit with Tolkien’s own line drawings and watercolors. Catlin has created whimsical pictures that capture the innocent wonder of a reader first entering Middle-earth and going along on Bilbo’s journey. Kids will love these pictures because they’re clever, moving and funny. And adults will love them for the same reason.

And what a Smaug-like treasure trove is to be found in this handsome clothbound hardback! There are 150 of Catlin’s pieces in this book. Most of them are neat little watercolor, ink and pencil pictures that appear in random places throughout the story, oftentimes with text wrapping around the image.

Because there are so many pictures in this edition (the most of any edition of The Hobbit in print) we get to see little tidbits that usually get overlooked by artists—Gollum recalling a vision of “eggses” (Catlin shows blue robin eggs inside a sinister looking thought bubble); goblins picking up Bilbo’s buttons with humorous expressions on their piggy-bat faces; Bilbo dreaming of dancing black bears while asleep at Beorn’s; a flash forward (described by Tolkien) of Smaug’s bones on the bottom of the Long Lake; the crown of red leaves and berries in Thranduil’s hair; a sign announcing the sale of Bilbo’s belongings that you can read in a flowing script “Messrs Grubb, Grubb, and Burrowes would sell by auction the effects of the late Bilbo Baggins,” etc. I could go on and on about these glorious little details.

There are over a dozen full page illustrations too, and they are marvelous. There is one showing the trolls after they’ve been turned to stone that evokes the fanciful work of Cor Blok; and the dinner party at Beorn’s with his animal waitstaff (a sheep’s back makes an excellent stand for a serving tray). The image that I like best is a lovely close up of Smaug, snoozing smugly atop his heaps of gold and jewels, crowns and caskets.

Some of the more unconventional pictures are my favorites. There’s one of Thorin as he’s floating down the Forest River—and we know it’s him inside because we get to see through the side of the barrel, as though with X-ray vision, to the cramped and grumpy Dwarf crammed inside. I also like the way she illustrated Bilbo whenever he puts on the One Ring: he’s drawn in black and white, as though he were a ghost.

Catlin did a masterful job of capturing the personalities of Bilbo and Gandalf. The wizard is especially expressive and I love the picture of him displaying the map of the Lonely Mountain to Thorin & Co. and Bilbo at Bag End. There’s also a cool image of Gandalf in disguise at the camp of the Elvenking, and another of him smoking his pipe and blowing colored smoke rings with a perfectly roguish look on his face.

If I haven’t already convinced you to buy this version of The Hobbit and add it to your collection, then I give up. All I can say is that I believe that J.R.R. Tolkien himself would have loved these illustrations because they are in the same spirit as his own pictures for The Hobbit (and even his Father Christmas Letters). Catlin has done herself proud, and publisher David Brawn of Harper Collins UK made an excellent choice when he picked her to illustrate this beautiful edition.

The Hobbit illustrated by Jemima Catlin will be available in the United States on October 1st.

You can follow Ms. Catlin on Twitter @jemimacatlin